2 October 2025

Written by Pierre Sutter, Nitidae

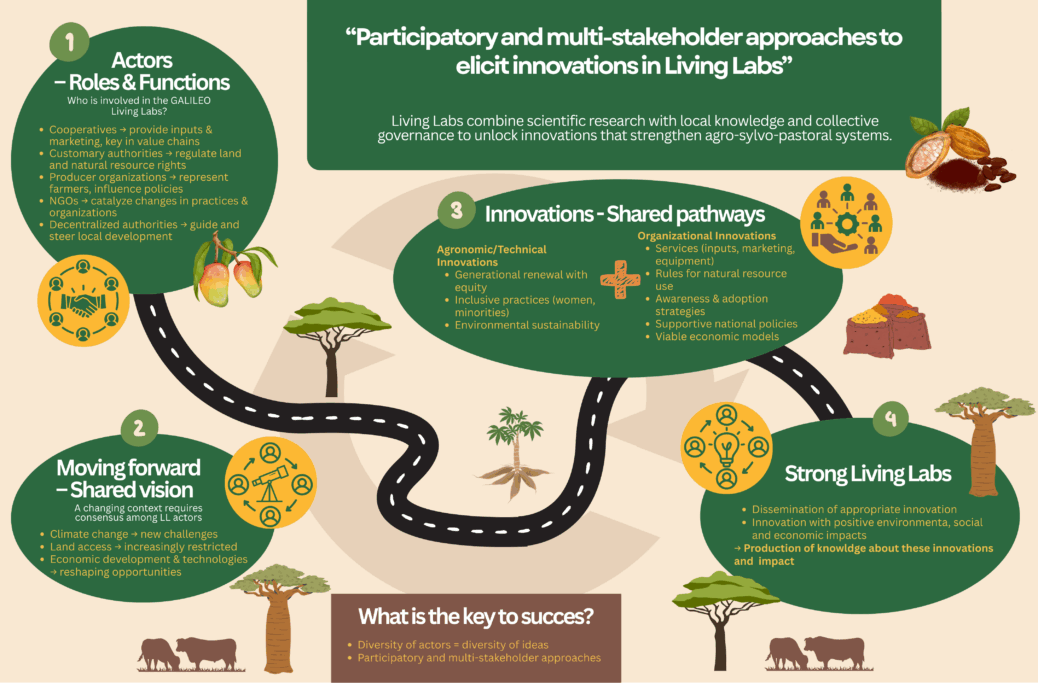

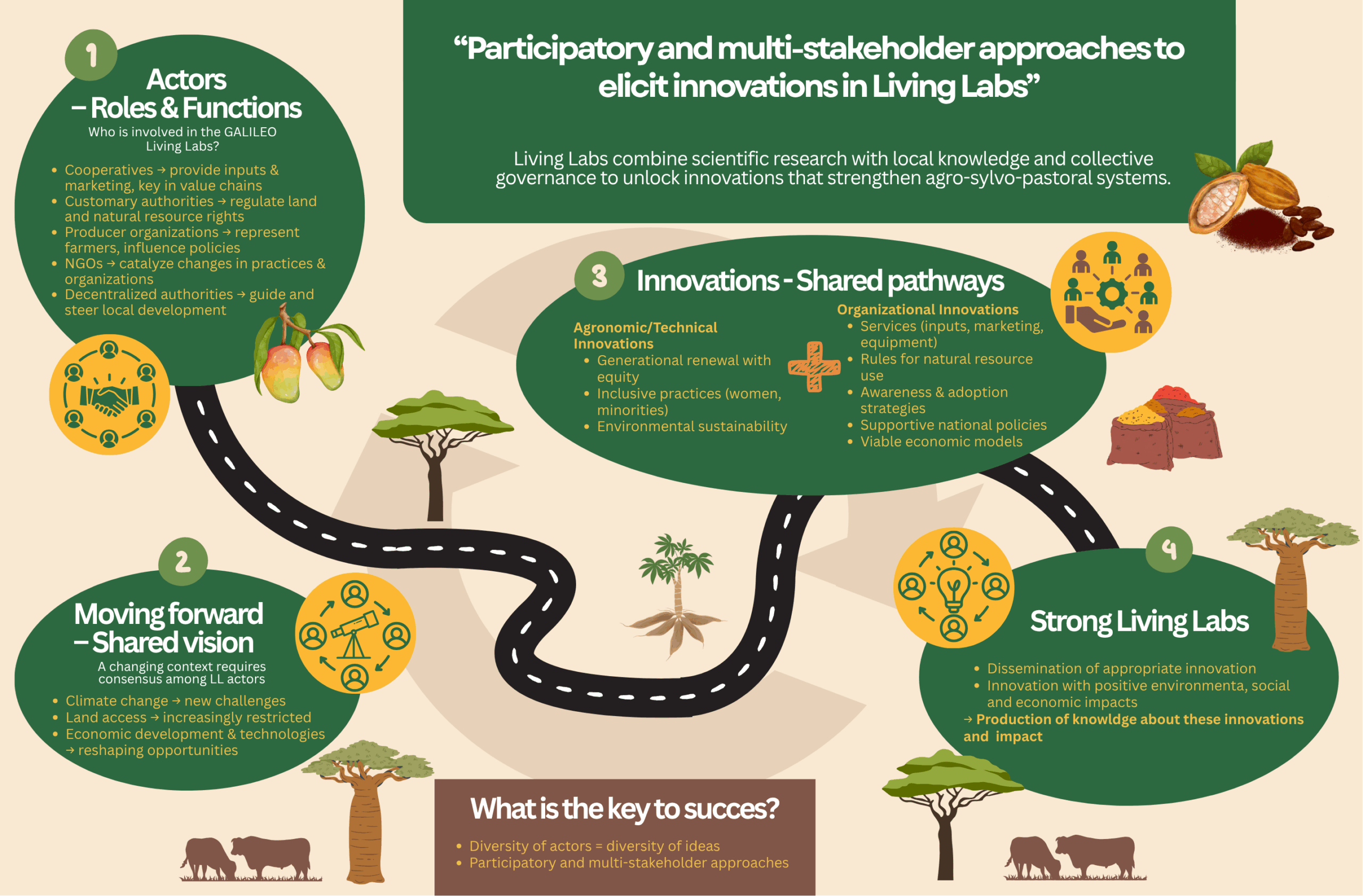

Participatory and multistakeholders approaches to elicit innovations in Living Labs:

The GALILEO approach

GALILEO project brings together 22 partners spanning from research stakeholders (research centres and universities) to producer organizations, private sector stakeholder and national and international NGOs from 11 different countries. This blend of partners is strengthening the link between researchers and other stakeholders and brings together a variety of fields of expertise, combining scientists measuring biophysical flows with social science researchers working at different levels from field/household levels to the territory/sector/community levels.

However, all these people working together on these actions are only the visible face of the project. Behind this impressive partnership, lies a multitude of actors who will be involved in the project’s implementation, yet not known at this stage of the project.

The GALILEO Living Labs (LLs) are multi-stakeholder mechanisms that bring together all the actors with an interest in agroforestry in the target areas. These are private or public actors, individuals or groups, representing a variety of and sometimes divergent interests. These actors are currently being identified, and the LLs will remain open structures throughout the project duration. Thus, cooperatives, input sellers, traders, representatives of farmers’ organizations, traditional chiefdoms, management committees, agricultural extension agents, environmental protection agents, representatives of local authorities, and many others. All these stakeholders must be included in the LL exchanges to consider changes to the challenges facing the region and its industries.

Each GALILEO LL will require an ad hoc governance to carry out the participatory activities. This governance ensures that the initiative remains on track and consistent in its goal of strengthening agroforestry systems and understanding them. To this end, the LL governance must allow stakeholders involved in the LL to contribute, ensuring that no one initiative takes over, facilitating the integration of endogenous and research knowledge to fuel innovative co-creation processes.

It is also important to remember that each type of structure has specific functions which, when properly fulfilled, establish their legitimacy. Each stakeholder in the LL has one or more contributions according to their roles or mandate. For example:

-

Cooperatives serve producers: input supply services and services for selling members’ production are the most important, making them key players in the value chains.

-

Local customary authorities and development committees (or equivalent structures with other names) are responsible for establishing and enforcing the rules that govern life in rural areas: land tenure, tree ownership, rights of access to natural resources, etc. They are therefore the key players in these areas.

-

Producer organizations, such as councils and unions (FOs), represent producers in a given sector or region in their interactions and discussions with public authorities, with a view to influence the country’s agricultural policies, for example by defending a particular type of family/small-scale, agroecological agriculture, or institutionalizing changes.

-

NGOs and associations tend to play a temporary operational role, bringing about change in existing organizations, agricultural practices, etc.

-

Decentralized authorities (e.g. water and forestry agents, agricultural extension agents) have a role in steering these changes.

Recognizing the role of other structures involved in LL and the project allows each to play a role where it is most legitimate and effective.

Where are we going together?

If, as the saying goes, “Alone we go faster, together we go further,” going far is good, but in what direction?

Especially since we are never in a static situation. The context is constantly changing: the climate is changing, access to land is increasingly restricted, the economy is developing, and new technologies are emerging.

While predicting the future is always a tricky exercise, it is important that the stakeholders involved in LLs have a shared vision of the direction in which the context is evolving. It is on the basis of this projection, this scenario, that we can reach a consensus on a common goal, a scenario in which the future looks brighter.

How do we walk in step?

The desired changes call for innovation. However, relevant and replicable innovation is rarely a technical change that a producer, taken as an isolated actor, can adopt alone. It necessarily involves simultaneous changes in the organization of sectors and territories; organizational innovations that must be established simultaneously. Therefore, a parallel reflection must be carried out around innovation:

-

What agronomic/technical innovations are desirable for all stakeholders in the region and the sector?

-

Innovations that enable the renewal of agricultural generations under conditions of equity (access to land, resources, control over the sector, etc.)

-

Innovations that do not harm any group: types of producers, women, and minorities.

-

Innovations that have a positive impact on the environment

-

-

What organizational innovations will enable this agronomic innovation to be replicable and viable?

-

What services should be considered (supply of equipment, inputs, marketing plans, labelling)?

-

What rules governing the use of natural resources (land, water, forests, etc.) need to be adapted or modified?

-

How can awareness of this innovation be raised to ensure its widespread adoption?

-

How can the national regulatory framework evolve to promote this innovation?

-

What are the economic models for these organizational innovations?

-